HE PLAYS THE VERIZON WIRELESS Theatre in Houston on November 30, and the Majestic Theatre in Dallas on December 1.

They may not be songs about Texas, but Tony Joe White wrote Rainy Night in Georgia and Polk Salad Annie while living in Corpus Christi. Currently on tour opening for Joe Cocker, the Louisiana native chats about old times, his new record label, and the Texas musician who first inspired him to play guitar.

texasmonthly.com: You just got back from Europe. Where did you go?

Tony Joe White: We started in Holland, Scotland, England, Germany, up to Austria...everywhere over there.

texasmonthly.com: All with Joe Cocker?

TJW: No, this was just me and my drummer. I always like to play on stage just with a drummer. For some reason my guitar playing is wilder and I'm able to sing in tune. There's a lot of freedom that way.

texasmonthly.com: Is that how you play when you're opening for Joe Cocker?

TJW: Yeah, same way.

texasmonthly.com: Has this drummer been with you for a long time?

TJW: Yeah, Boom-Boom, is what I call him. You know, he's got this big 'ol foot. He just lays it in there and it fits my guitar just right. He's been with me about 11 or 12 years. But on the Cocker tour, actually Jack, Joe's drummer is playing with me. I actually don't have but about thirty minutes when we're fronting. So Boom's gonna get a rest. He's been at it hard over in Europe with me.

texasmonthly.com: How long do you play when you're headlining?

TJW: Usually about an hour and a half, and then it ends up about two and a half. You know, they won't let you go. And you get caught up there and before you know it....

texasmonthly.com: Are the audiences in Europe different than they are here?

TJW: Not as far as the way they join me instantly. Some of the places are a lot bigger, but the crowds, no matter where, just become a part of the show. I come out first by myself and just get with the crowd. And they're hollering out all the old swamp tunes and I do requests. I do about thirty minutes that way and then we come out and kick it up another volume level and go.

texasmonthly.com: When you finish up with the Cocker tour are you going to do some more solo touring?

TJW: I will. I go to Australia for a blues festival in February that we play every year. When I come back to America a lot of things have been lined up.

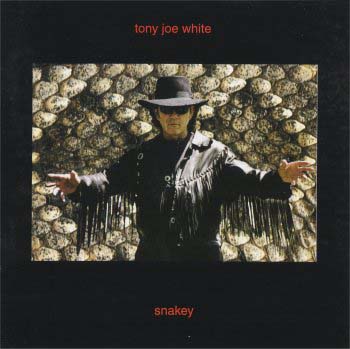

texasmonthly.com: You have a new label and a new record,Snakey. A lot of things going on?

TJW: The label is called Swamp Records. We had it in the makes for a good while, just my son, Jody, and me, and then all of a sudden we got the Web site going and all this stuff began happening, and the tour and I said, "Man, I'm going to have to go fishing sometime."

texasmonthly.com: I can relate. We have a quiet little place in the country in Southwest Louisiana where we go fishing or just hang around the fire and play guitar.

TJW: That'd be great! There's nothing better than a good fire, a good cold beer, and just sitting out and being still. In fact, that's how I write, really. When I get an idea or something on the guitar, a title or a line, I usually go back out in the woods behind the house and build a fire, get a couple of six packs of beer and my acoustic guitar, and just sit and stare into the fire and all of a sudden something will come.

texasmonthly.com: WhenPolk Salad became a hit, weren't you living somewhere in South Texas?

TJW: Corpus Christi. I lived there for twelve years. When I left Louisiana I went straight to Kingsville then Corpus. I was really into it. I mean barefoot all the time and brown and fishing out on Padre Island. And playing in the clubs at night. I thought, "Man, this is already it." I actually started writing down there. I was just about 19 when I first went there, right after high school. And I started playing in the clubs there six nights a week and, you know, that's where I first wrote Polk Salad Annie and Rainy Night in Georgia, there in Corpus.

texasmonthly.com: Where did you record?

TJW: We saved up a little bit and took a week off, and I headed to Memphis, but for some reason—it seemed too big or something for me—I went on to Nashville. I got hooked up with a guy at a club the first night, a bouncer, who knew a guy who knew a guy that had a telephone number. About five guys down, you know? Most everybody I met that afternoon, when they asked what kind of music I played, I said, "It's kind of bluesy and kind of swampy." And they said, "You drove a long way for nothing." So anyway the next day I had this phone number. It was a guy named Bob Beckham, and he was a publisher and also a partner with Monument Records. And he also had a bad tequila hangover and did not want to see anybody. His secretary, after talking to me for awhile got on the phone to him and said, "I think you should see this guy. He drove all the way from Corpus Christi." And Beckham said, "I don't care how far he drove." And she said, "I think you should see him." I don't know what it was, there's a look you get when you really want somebody to hear you play, you know? So he came out and we went in this little room together and I sung him a piece of Polk and I sang Roosevelt and Ira Lee and a few others. And he started coming out of his hangover. It went almost straight from there to the company. We got a deal and came back two weeks later and I started recording. Which, in this day and time, would not happen. In fact, it wouldn't have happened then except that he was the only man in town that would have listened to any kind of blues at all.

texasmonthly.com: You sing a lot about racial relations in the South, like in the songLaura and Willie Mae. What is your sense of how things were? Some say that they were actually better in the South than....

TJW: Oh yeah, especially back then. The only way to describe it would be like, slow molasses floating across the ground. The times were slow and easy and we all worked together, picking cotton or working in the field and then sitting out at night on somebody's porch with guitars and playing the blues. We never thought about who was one way or the other. But like that song says that changed too. But there's still a different coolness down South between whites and black people.

texasmonthly.com: Do you think it's different in the North?

TJW: Yeah. They don't get it. And you know, they don't have to.

texasmonthly.com: When you talk about growing up, was that in Oak Grove, Louisiana?

TJW: Yeah, well it was right outside of Oak Grove in a little place called Goodwill. We had a church house, a cotton gin, and two stores.

texasmonthly.com: What was your family like?

TJW: Well my father was a farmer, and I had five sisters and one brother. I'm the youngest. All of the girls played piano and guitar and sang. That's all I heard till I was 14 or 15 and I really wasn't into it. I was just listening to mom and dad and them and it was great to hear them but nothing that was moving me. And then my brother brought home an album by Lightnin' Hopkins. And I heard that man playing, just him and his guitar and foot pattin'. I was about 15. I starting taking dad's guitar and locking myself in the bathroom at night and play it.

texasmonthly.com: After you started making records did you ever go back to Corpus Christi?

TJW: I didn't leave Corpus till about 1971, and then I moved to Memphis. In fact, I moved when Poke hit finally. A lot of things started happening and people were cutting my songs. I felt caught up in little whirlwind type thing that I didn't like. It was about '72 and I said, "You know, this ain't why I play music." It had gotten to where I really wasn't writing and I was constantly traveling and doing interviews. So I took my family, my wife and two kids, and we moved up to the Ozark Mountains in Arkansas. I had bought some land there, had a few horses, creek right behind the house, and I just put the kids in school there in this little rural town—wasn't even a town. God, it was far so out you couldn't even imagine. In fact, if it rained overnight like a barrel on a chain to get across the river. Anyway, I got to writing again and got it lined out and got back into the thing a year or two later. But right at that particular time I said, "I gotta ease back."

texasmonthly.com: Did you find what you were looking for?

TJW: Yeah, a lot of good songs popped out of that deal. And just the quietness, you know. I still got that place.

texasmonthly.com: Was that place shown in the film,Searching for Tony Joe?

TJW: In the film, that's my place right outside of Franklin, Tennessee. On a little lake there. Yeah, I tell you, those boys...they're all from Austin. We had the best, coolest times, just sitting on the porch at night playing. One of them is a real good guitar player.

texasmonthly.com: I really enjoyed that film.

TJW: I think it won the Detroit film award. What I liked about it is the way they filmed themselves amongst people that they met along the way. Like when they went in that little store in Oak Ridge, I think it was in the wrong town. Anyway, they held my picture or something to a woman and asked if she knew me, and she said, "Is he a missing person?" In a way it's as good as Easy Rider, without the violence!

texasmonthly.com: When you started writing songs for other people, kind of like the woman said, you were something of a missing person for a while. You were around but nobody knew....

TJW: It's kind of like getting to be in the thing but yet not having to really pay the price. I was in the background, getting to play guitar and stuff with what I call my heroes. Tina Turner, Joe Cocker, Elvis Presley, people like that. And getting to actually record. Then I'd go out and play a few clubs when I wanted and go to Europe a couple times of year, and Australia. So it was kind of like people didn't know if I was still there or where I was.

texasmonthly.com: What are your plans for Swamp Records?

TJW: I think there's probably two or three more albums that are actually cut. The only thing I know is we plan on trying to play cool music and get to the people, which is a very lucky thing that we can do in this way.

texasmonthly.com: Are you going to sign any other artists to your label?

TJW: Jody, my son, was talking about it. And he's the one that kind of runs things. We hope to find maybe two or three blues, rock, or someone we like. I'm sure he's going to go on that way with it. Me, I'm just kind of hanging and getting to play music and letting him take care of it.

texasmonthly.com: Is there anybody you want to work with that you haven't yet, or any other goals, things you'd like to do?

TJW: There are artists that I've worked with but I haven't actually recorded with. And there's two guitar players who are my favorites: Mark Knoffler and Clapton. We have talked a hundred times, traveled together and all that, but for some reason we haven't been in the studio yet, and we're thinking maybe this year we'll do it. And I'm also wanting to get Tina Turner back out. She's in the woods right now, like I did, you know? In a castle somewhere south of France. But I find it hard to believe that she would just shut that off. It's so beautiful. I'd like to try to get Tina to go in to a little studio and just bass drums, a B-3 organ and a little guitar, and do a little bluesy stuff and just cut it really raw. I don't know if she'll ever do it, but everybody's waiting for it.

texasmonthly.com: Do you ever get tired of playingPolk Salad Annie?

TJW: No, I haven't yet. It's one of those things where the audience gets caught up in it, and they start chanting it, and all of a sudden we'll hit it. I never play it the same way twice, so it's like a new groove. I have never really gotten tired of playing any of the tunes. If I've got a crowd, and we're going at it, it's like, you just sweat and let it roll.

November 2002

TexasMonthly.com

|

|

|

|